|

Type |

Suture |

Syndromic |

Name |

|

Primary |

Single suture |

Non-syndromic |

Scaphocephaly |

|

Non-syndromics |

Plagiocephaly |

||

|

Trigonocephaly |

|||

|

Brachycephaly |

|||

|

Oxycephaly |

|||

|

Multiple sutures |

Syndromics |

Crouzon |

|

|

Apert |

|||

|

Pfeiffer |

|||

|

Saethre- Chotzen |

|||

|

Secondary |

To storage disorders of mucopolysaccharides |

Hurler |

|

|

Morquio |

|||

|

To metabolic disorders |

rickets |

||

|

Hypothyroidism |

|||

|

To hematological disorders |

Polycythemia vera |

||

|

Thalassemia |

|||

|

To medication intake |

Retinoic acid |

||

|

Diphenylhydantoin |

|||

The types of craniosynostosis

Unicoronal Synostosis

Affected suture: coronal

Resulting deformity: anterior plagiocephaly.

Incidence: 1 in 10,000 (20% of all non-syndromic craniosynostoses)

Epidemiology: male to female ratio is 3: 2

Physical examination: Ipsilaterally, there is a widening of the palpebral fissure, elevation and anterior displacement of the ear, deviation of the nasal base towards the affected side, a prominent malar eminence and an elevation of the supraorbital recess.

Contralaterally, there is a frontal protuberance and the chin is usually deflected to the unaffected side.

Images: the harlequin orbit is present due to the lack of descent of the greater wing of the sphenoid. This deformity consists in the loss of the lateral orbital height with an elevation of the supraorbital recess.

Bicoronal Synostosis

Affected suture: coronal

Resulting deformity: turribrachicephaly

Incidence: 1 in 10,000 (20% of all non-syndromic craniosynostoses)

Epidemiology: male to female ratio is 1:1

Physical examination: the skull typically shortens, anteroposterior diameter and tends to have a widened forehead with hypoplastic supraorbital arches

Lambdoid Synostosis

Affected suture: Lambdoidea

Resulting deformity: posterior plagiocephaly.

Incidence: Rare, less than 3% of all non-syndromic craniosynostoses

Epidemiology: male to female ratio is 2: 1

Physical examination: Ipsilaterally, there is flattening in the occipital region, the ear moves downwards and backwards. Contralaterally, there is occipital prominence (Cohen et al., 2017).

The surgical management of craniosynostosis has evolved significantly over the years. At the end of the 19th century, craniectomies were performed, where the first procedures for craniosynostosis were reported, the objective was to release the fused suture and allow the restriction area to expand with the brain that was growing. In the 1970s (Hu et al., 2017), the objectives changed and not only surgical procedures were performed to release the areas of restriction, but also the aesthetic aspect of the skull was addressed. Cranial vault reconstruction techniques are introduced, using long incisions with extraction and reorganization of large bony flaps to create a normal head form. These were prolonged surgical procedures with greater blood loss, but achieved excellent results. In recent decades, less invasive surgical procedures have been introduced by adding new techniques and applications to achieve the same results obtained by more aggressive cranial vault reconstructions with less blood loss and shorter scars (Chesler et al., 2018; Pagnoni et al., 2014).

Among the surgical indications for the management of craniosynostosis, are (1) the correction of cranial deformity and (2) the treatment and/or prevention of increased intracranial pressure in order to prevent negative impacts on neurocognitive development and/or the visual disability of patients.

The surgical moment depends of multiple factors that include the type and severity of the synostosis, the surgical technique, the co-morbidities and also the preference of the surgeon. Most surgeons agree that surgical intervention is ideally done before 12 months of age (Brandel et al., 2018).

In general, early surgical intervention occurs between 2 and 3 months of age with minimally invasive procedures. Surgeries at an early age take advantage of the fact that the cranial bones are thinner and more flexible (Prada-Madrid et al., 2017). Surgical intervention in the first months of age could result in a less severe compensatory deformity and early and timely treatment of elevated intracranial pressure. A surgical intervention at more advanced ages (6 to 12 months of age) has the advantage that the cranial bones are harder to support surgical reconstruction, which allows a lower relapse (Jeong et al., 2017)

Many variables come into the decision-making process about the type of surgical intervention for non-syndromic craniosynostosis. They include the age of the patient, the location and degree of the deformity, the general health of the patient and the possible need to repeat the surgery (Joly et al., 2019)

In general, approaches such as endoscopic or linear craniectomy, are usually reserved for selected younger patients (less than 6 months of age) with mild deformities that affect only one suture (Balaji, 2017). More invasive approaches (remodeling of open cranial vault with fronto-orbital advancement) are generally used in older children (older than 6 months) who have more severe deformities that affect one or more sutures.

Surgical procedures often involve the removal of the affected bones, with osteotomies and adjustments of these bone flaps which are remodeled, are placed again on the exposed dura in a more anatomical position and stabilized using different methods (suture, wire, plates, screws). The modern trend of fixation involves resorbable plate systems that are beneficial in that regard, because first, it is not necessary to remove them, as they are reabsorbed over time and second, have less probabilities than titanium plates to interfere with facial growth. The main features of any operation for craniosynostosis include: release of the fused sutures and remodeling of the hypoplastic and compensatory anomalies of the craniofacial skeleton (de León, 2011).

The surgical techniques commonly used are: reconstruction of the anterior, posterior and total cranial vault, fronto-orbital advancement, minimally invasive techniques, endoscopic craniectomy with the use of a helmet, assisted craniectomy or with the use of a spring, distraction of the cranial vault by osteogenesis.

Each of these techniques are used for the correction of craniosynostosis, there are techniques that can be used more frequently depending on the type of craniosynostosis, for the surgical management of complex craniosynostoses, recommendation is directed to perform an interdisciplinary management, since the approach is holistic with decreased risks as well as better functional and aesthetic results (Kajdic et al., 2018).

Next, the interdisciplinary surgical management that was performed in patients with various cases of craniosynostosis will be related.

Case #1 (premature synostosis unilateral coronal suture)

Frontal-orbital advancement unilateral

Images

Skull CT plus 3D reconstruction

Planning

Positioning and marking

Approach

Case #2 (Brachicephaly)

Planning

Skull CT plus 3D reconstruction

Positioning

Approach

Case # 3 (Saethre Chotzen syndrome)

Coronal flap

Osteotomy lateral wall of the orbit

Orbital osteotomy

Craniofacial disjuncture

RED distractor placement

First week of distraction

Third week of distraction/ consolidation

Distractor removal

Case # 4 (Pfeiffer syndrom)

Monobloc advance osteogenic distraction

Craniotomy

Craniofacial disjuncture

Stage of distraction (craniofacial advance)

Case # 5 (Cranio?facial cleft of Tessier)

Approach

Case # 6 (Kabuki syndrome)

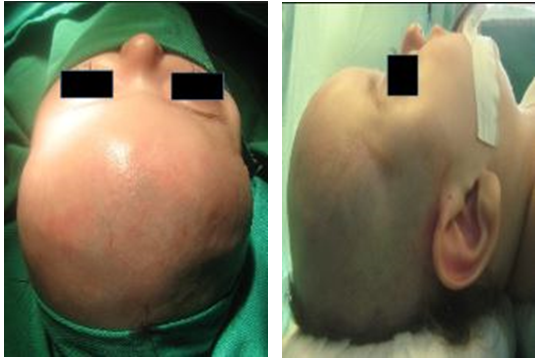

Case # 7 (Kleeblattschädel syndrome)

Preoperative CT in first time

Skull CT plus 3D reconstruction

CT postoperative in first time

Positioning in second time

Approach

Discussion

The craniosynostosis, are complex and broad entities in their approach, which not only hinders their diagnosis but also their management; At present, and as it has been previously referenced, surgical management is not only performed for aesthetic purposes, but also functional, since it is demonstrated that adequate surgical management and at the proper time, decreases the appearance of neurological sequelae secondary to late management of craniosynostosis

Within the objectives of surgical management are: correct anomalies (functional and aesthetic), restore normal spatial relationships (of the skull, brain structures and vascular structures), correct alterations of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics and venous circulation and finally, reorientate normal growth vectors.

Therefore, from our experience, we can leave some messages for those interested in the study of childhood neurosurgery:

- The surgical decision is not easy

- Is necessary to always have support from the interdisciplinary team

- Parental support in these cases is essential to make decisions to define expectations that they have in surgery

- Develop processes for patient follow-up and thus generate: a. institutional memory b. institutional experience c. fertile ground for residents

- Most appropriate surgical technique will depend on: a. neurosurgeon experience b. interdisciplinary team experience c. therapeutic and social synergism to improve the impact on surgery patients.

References:

Mundinger GS, Rehim SA, Johnson O, Zhou J, Tong A, Wallner C, Dorafshar AH. Distraction osteogenesis for surgical treatment of craniosynostosis: a systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg 2016; 138: 657-669.

Flaherty K, Singh N, Richtsmeier JT. Understanding craniosynostosis as a growth disorder. WIREs Dev Biol 2016; 5: 429-459.

Pérez IS, Monterroza JF, Vergara AC. Craneosinostosis: Revisión de literatura. Universidad Y Salud 2016; 18: 182-189.

Garrocho-Rangel A, Manríquez-Olmos L, Flores-Velázquez J, Rosales-Berber MÁ, Martínez-Rider R, Pozos-Guillén A. Non-syndromic craniosynostosis in children: Scoping review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2018; 23: e421- e428.

Cohen S, Frank R, Meltzer H, Levy M. craniosynostosis. Handbook of Craniomaxillofacial Surgery Downloaded 2017; pp: 343-368.

Morris LM. Nonsyndromic craniosynostosis and deformational head shape disorders. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am 2016; 24: 517-530.

de León FC. Craniosynostosis. I. Biological basis and analysis of nonsyndromic craniosynostosis. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex 2011; 68: 333-348.

Hu CH, Wu CT, Ko EW, Chen PK. Monobloc frontofacial or Le Fort III distraction osteogenesis in syndromic craniosynostosis: three-dimensional evaluation of treatment outcome and the need for central distraction. J Craniofac Surg 2017; 28: 1344-1349.

Chesler D, Bram R, Antwi P, Timberlake AT, DiLuna ML, Kahle KT. Non-syndromic single-suture craniosynostosis in triplets. Child's Nervous System 2018; 34: 1241-1245.

Pagnoni M, Fadda MT, Spalice A, Amodeo G, Ursitti F, Mitro V, Iannetti G. Surgical timing of craniosynostosis: what to do and when. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery 2014; 42: 513-519.

Brandel MG, Dalle Ore CL, Reid CM, Zhu W, Lance S, Meltzer H, Gosman AA. Distraction osteogenesis for unicoronal craniosynostosis: Rotational flap technique and case series. Plast Reconstr Surg 2018; 142: 904e-908e.

Prada-Madrid JR, Franco-Chaparro LP, Garcia-Wenninger M, Palomino-Consuegra T, Stanford N, Castañeda-Hernández DA. A Surgical technique for management of the metopic suture in syndromic craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg 2017; 28: 675-678.

Jeong WS, Altun E, Choi JW, Rah YS. Comparison of endocranial morphology according to age in one-piece fronto-orbital advancement using a distraction in craniosynostotic plagiocephaly. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery 2017; 45: 1394-1398.

Joly A, Croise B, Travers N, Listrat A, Pare A, Laure B. Management of isolated and complex craniosynostosis residual deformities: What are the maxillofacial tools?. Neurochirurgie 2019; 65: 295-301.

Balaji SM. Unicoronal craniosynostosis and plagiocephaly correction with fronto-orbital bone remodeling and advancement. Ann Maxillofac Surg 2017; 7: 108-111.

Kajdic N, Spazzapan P, Velnar T. Craniosynostosis-Recognition, clinical characteristics, and treatment. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2018; 18: 110-116.